The Arctic and Alaska

The Arctic is thawing very rapidly, documented by new reports from scientists and arctic natives. The Arctic Climate Impact Assessment was released in late 2004, and shows changes from the ice at the North Pole to animals and human settlements. More recent reports from Greenland show outlet glaciers moving meters per hour and rapidly thinning. The Arctic Ocean ice cap is shrinking in summer to the smallest it has ever been in modern measurements, and even winter cold has not been refreezing it as extensively as before. That sea ice is habitat for the polar bear. Declines in bear nutrition, birth weight and survival have moved the U.S. government (urged by three environmental groups) to propose the bear be named a species threatened with extinction.

Below and on linking pages, are reports on the latest science and warming effects across Alaska and parts of the Arctic. For more on Arctic natives, please see the Arctic page. Also see Glaciers for more on Greenland and Alaska glaciers.

Pushing the Boundaries of Life: Alaska

The listing of polar bears as threatened under the U.S. endangered species act will name global warming as the main threat, a first. The reduction of the permanent Arctic sea ice by 14 percent since the 1970s is causing not only feeding and breeding difficulties, but also drownings and apparent cannibalism among bears. The listing should be official by the end of 2007. For more information, see Center for Biological Diversity. Scientists are just beginning to see the effects of climate change on other Arctic wildlife. Caribou give birth at specific times and locations, making them susceptible to changes in weather and vegetation. Studies show that the tundra is now blooming slightly earlier and that it is affected by drier summers and heavier winter snow.

The listing of polar bears as threatened under the U.S. endangered species act will name global warming as the main threat, a first. The reduction of the permanent Arctic sea ice by 14 percent since the 1970s is causing not only feeding and breeding difficulties, but also drownings and apparent cannibalism among bears. The listing should be official by the end of 2007. For more information, see Center for Biological Diversity. Scientists are just beginning to see the effects of climate change on other Arctic wildlife. Caribou give birth at specific times and locations, making them susceptible to changes in weather and vegetation. Studies show that the tundra is now blooming slightly earlier and that it is affected by drier summers and heavier winter snow.

Biologist Gus Shaver at one of his experimental plots at Toolik Lake, Alaska, monitors increased birch growth due to experimental fertilization and global warming. Shaver says the results of his experiment suggest that warming eventually will promote the growth of birch at the expense of sedges, forbs, and other plants that caribou and other wildlife favor as food sources. During an initial 15-year study (1981-95, which included the warmest decade on record) the sedge Eriophorum decreased by 30 percent while birch biomass increased, even in control plots. In 2002 Shaver reports the growth of birch has changed the ecology of tundra in some plots by covering and killing moss with large amount of leaf litter.

Biologist Gus Shaver at one of his experimental plots at Toolik Lake, Alaska, monitors increased birch growth due to experimental fertilization and global warming. Shaver says the results of his experiment suggest that warming eventually will promote the growth of birch at the expense of sedges, forbs, and other plants that caribou and other wildlife favor as food sources. During an initial 15-year study (1981-95, which included the warmest decade on record) the sedge Eriophorum decreased by 30 percent while birch biomass increased, even in control plots. In 2002 Shaver reports the growth of birch has changed the ecology of tundra in some plots by covering and killing moss with large amount of leaf litter.

The great loss of ice from the Arctic, which includes not only the polar sea ice cover but also thawing glaciers and tundra permafrost, has other major implications. One of the most important is that dark open water and tundra absorb much more solar heat than white ice and snow. This is a "feedback loop" that will make changes happen faster.

Another large effect in the Arctic is a freshening of the Arctic Ocean. In late 2002, geochemist Bruce Peterson of the Marine Biological Lab in Woods Hole, MA, and his collaborators in the US and Russia, showed that the major rivers of Siberia and Eurasia are discharging much more water now than in the 1930s. This not only meets the predictions of an effect of climate change, but indicates the scale of change affecting the Arctic.

In late 2002, geochemist Bruce Peterson of the Marine Biological Lab in Woods Hole, MA, and his collaborators in the US and Russia, showed that the major rivers of Siberia and Eurasia are discharging much more water now than in the 1930s. This not only meets the predictions of an effect of climate change, but indicates the scale of another source of added fresh water into the Arctic.

In late 2002, geochemist Bruce Peterson of the Marine Biological Lab in Woods Hole, MA, and his collaborators in the US and Russia, showed that the major rivers of Siberia and Eurasia are discharging much more water now than in the 1930s. This not only meets the predictions of an effect of climate change, but indicates the scale of another source of added fresh water into the Arctic.

So what is happening to all this fresh water from increased river flow, melting glaciers and shrinking sea ice? It mixes into the Arctic Ocean and the less salty Arctic water flows south around Greenland, to the source of some of the greatest ocean currents.

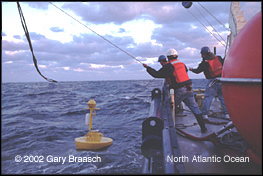

The interplay of ocean currents in the North Atlantic is very important to climate. Here, between Labrador and Scandinavia, the Gulf Stream brings a huge flow of water from the south, helping warm Europe as it gives up its heat. This water sinks as it cools, to flow back south again in the deep Atlantic. This plunging down of millions of tons of water per second helps propel what has been termed the Great Ocean Conveyor, a system of huge currents transferring heat throughout all oceans and influencing climate.

The interplay of ocean currents in the North Atlantic is very important to climate. Here, between Labrador and Scandinavia, the Gulf Stream brings a huge flow of water from the south, helping warm Europe as it gives up its heat. This water sinks as it cools, to flow back south again in the deep Atlantic. This plunging down of millions of tons of water per second helps propel what has been termed the Great Ocean Conveyor, a system of huge currents transferring heat throughout all oceans and influencing climate.

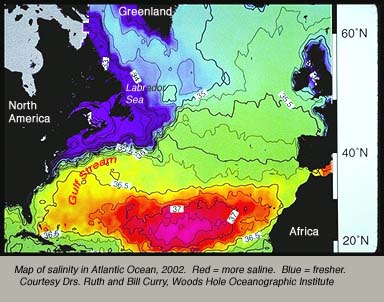

One key to this system is that the Gulf Stream water becomes more dense as it gives up heat, and it sinks. But the added fresher water coming down from the Arctic is much less dense, and floats on top of the North Atlantic.

Is there enough new fresher water from the Arctic to prevent the Gulf Stream water from sinking to help drive the conveyor of currents? According to recent studies by Dr. Ruth Curry and colleages at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, there is more fresher water in the area than ever measured before. Already sinking rates in some locations are 20 percent less than in the 1970s.

The northern waters are getting fresher while the southern waters (near equator) are increasing in salinity. Curry says this indicates a change in the climate with more precipitation and ice melt in the north and much stronger evaporation in the south. In other words: "Global warming."

The northern waters are getting fresher while the southern waters (near equator) are increasing in salinity. Curry says this indicates a change in the climate with more precipitation and ice melt in the north and much stronger evaporation in the south. In other words: "Global warming."

Scientists are concerned that the point at which the current Conveyor does begin to slow may be near. Other current research shows the Gulf Stream is not the prime moderator of European temperature (westerly winds play a larger role). Yet climate in Europe and NE North America could chill if the ocean current slows dramatically. This is the jumping off point for a recent Pentagon planning report about possible international unrest caused by climate change, and for the movie "The Day After Tommorow." Scientists say disruptive change is coming -- but much more slowly than depicted in these scenarios.

More Climate Change in Alaska 2 >>

Photographs from the World View of Global Warming are available for license to publications needing science photography, environmental groups and agencies, and other uses. Stock photography and assignments available.

Please contact requestinformation@worldviewofglobalwarming.org or Gary Braasch Photography (503) 699-6666.

Use of photographs in any manner, in part or whole, without permission is prohibited by US copyright law. These photographs are registered with the US Copyright Office and are not in the Public Domain.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น